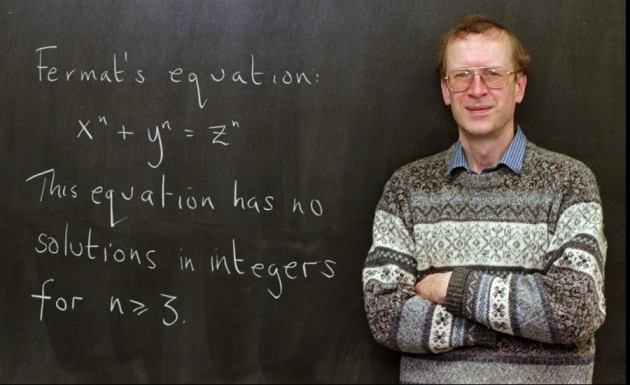

One of the most fundamental theorems that we learn in high school is the Pythagorean Theorem, which states that in a right-angle triangle, the sum of the squares of the two shorter sides is equal to the square of the longer side, i.e., \(a^2+b^2=c^2\), where a,b, and c are integers. There are infinitely many solutions for this when a,b, and c are integers. However, when we deal with the case where, instead of 2, it is an integer exponent greater than 2, things start to get a bit weird. Around 1637, Pierre de Fermat claimed that he had a marvelous proof that no three positive integers a,b, and c can satisfy the equation \(a^n+b^n=c^n\) for any integer greater than 2. This problem was commonly referred to as Fermat's Last Theorem. Here's a fun fact: Fermat scribbled this claim in the margin of his copy of an ancient Greek mathematics book, adding that the margin was too narrow to contain his proof. Most mathematicians believe Fermat was probably mistaken—he likely had a proof that worked for specific cases (like \(n=4\), which he did prove correctly) but thought it worked for all exponents, or he had a flawed proof that he mistakenly believed was correct (see NSF article). Although Fermat claimed that he solved it but there was no evidence of it. In fact, it took more than 350 years for Andrew Wiles to finally prove Fermat's Last Theorem in 1994. The proof was very complicated and used a lot of modern mathematics like elliptic curves and modular forms. The interesting question was why a tiny change in the exponent from 2 to 3 made such a huge barrier?

In 1985, Masser and Oesterlé proposed a conjecture known as the abc conjecture. The conjecture deals with three positive integers a, b, and c that are coprime (meaning they share no common prime factors) and satisfy the equation \(a + b = c\).

Let's look at a simple example. Take a = 2, b = 3, so c = 5. Here, \(2 + 3 = 5\). Notice that all three numbers are coprime—they don't share any prime factors.

To understand the abc conjecture, we need to know about the "radical" of a number. The radical of a number is the product of all its different prime factors, but we only count each prime once. For example, the number \(16 = 2^4\) has radical 2 (just the prime 2, counted once). The number \(12 = 2^2 \times 3\) has radical \(2 \times 3 = 6\).

Now, here's what the abc conjecture says. When you have three coprime numbers where \(a + b = c\), you calculate the radical of the product \(abc\). The conjecture claims that c is usually smaller than this radical raised to some power.

What does "repeated small primes" mean? By "small primes," we mean primes like 2, 3, 5, 7 (small numbers). By "repeated," we mean the same prime appears many times as a factor. For example, \(2^{10} = 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2\) means the prime 2 is repeated 10 times. The number \(2^{10} \times 3^5\) means the prime 2 is repeated 10 times and the prime 3 is repeated 5 times. The key insight is this: if a and b are both made of the same small primes (like 2 and 3) raised to high powers, then c cannot also be small—it must be relatively large. For example, if \(a = 2^{10} = 1,024\) and \(b = 3^{10} = 59,049\), then \(c = 60,073\). Notice that a uses only the prime 2 (repeated 10 times), and b uses only the prime 3 (repeated 10 times). Even though we're only using the small primes 2 and 3, the result c is quite large. The abc conjecture says this pattern usually holds: when a and b are built from the same small primes raised to high powers, c tends to be large.

Why does this matter for Fermat's Last Theorem? If the abc conjecture were true, it would immediately show that equations like \(a^n + b^n = c^n\) are impossible for \(n > 2\), which would trivially prove Fermat's Last Theorem.

Shinichi Mochizuki, a mathematician from the RIMS of Kyoto University, made an astonishing claim in 2012 that he had successfully proven the abc conjecture by relying on his own invention: Inter-Universal Teichmüller Theory (IUTT). This theory does not resemble other proofs; rather, it is akin to introducing a completely new set of rules for the operation of numbers. The biggest challenge to proving abc is to link two very basic characteristics of the number set: its additive structure (\(a+b=c\)) and its multiplicative structure. In regular math, it is almost impossible to completely separate these two sides for comparison. IUTT comes up with a different viewpoint: Don't 'combine' them; 'isolate' them. The method behind that is to virtually divide one mathematical object into multiple individual 'realms' (Hodge Theaters). The Additive Realm is tailored to deal with the equation \(a+b=c\) very efficiently, while the Multiplicative Realm is designed to tackle the prime factors very efficiently. So, the proof goes on by transferring the arithmetic object through one universe to another via a special bridge known as a theta-link.

The huge complexity and unconventional nature of IUTT made it impossible for most mathematicians to verify the proof. Mochizuki submitted his papers, but the common peer review process was not able to reach a consensus since only a limited number of people comprehended the new mathematics. This is where the dispute became personal and polarizing. In 2018, two eminent Western arithmetic geometers, the Fields Medalist Peter Scholze and Jakob Stix, spent several days in Kyoto discussing the work with Mochizuki (see Quanta Magazine report). They came back to declare they had discovered a significant logical flaw in the proof, which was particularly concerning a crucial technical step called Corollary 3.12. Scholze and Stix asserted that in this step, Mochizuki is drawing a comparison between two instances of the same mathematical object, which, notwithstanding the "re-initialization," are not really independent enough for the transformation to be valid. To put it simply, the object had not really lost its additive history when it was being studied in the multiplicative domain.

This perspective became the leading view among number theorists outside Mochizuki's narrow circle: the proof was incorrect, and the abc conjecture is still open. On the other hand, Mochizuki and his allies, including Kirti Joshi, wholly disagree, claiming that Scholze and Stix were simply not able to conceive the most elementary notions of IUTT, especially the significance of the new labels and species. Since that time Joshi has released his own series of papers in which he says he has fixed and completed Mochizuki's work, and claims that structurally IUTT is actually correct. Interestingly, despite Joshi coming to his defense, Mochizuki has reportedly been dismissive of Joshi's corrections by saying the work needed no fixing and was correct all along. Even though the main papers were formally published in 2021, the entire mathematical community has not bought into either side, and one of number theory's most important conjectures remains open.